We argue that director tenure should be recognised and managed by boards as a risk, the same as any other risk capable of impacting organisational performance.

Complementing a directors legal and fiduciary duties, boards have expectations of directors. Those expectations will often be articulated in board charters, codes of conduct and other relevant board policy. Managing director tenure in line with those expectations, the strategic direction of the business, any constitutional requirements and board policy, is imperative to ensure board renewal takes place in a way that builds organisational resilience and independent decision making.

Many boards can provide examples of directors who have outstayed their welcome and may be having a negative impact on both the board and the business. Many other boards can also provide good examples of directors who have reached their term limits and must leave the board despite being valuable contributors.

The common challenges in dealing with director tenure include:

- constitutions with no director term limits;

- no board renewal policy;

- no succession planning;

- no board skills matrix;

- self-interested directors, or those lacking self-awareness;

- no enforceable director letter of appointment; and

- inadequate or no board and individual director evaluations.

The ASX Corporate Governance Principles and Recommendations, 4th Edition, February 2019, will be embedded in every director’s mind and Principle 2 ‘Structure the board to be effective and add value’ is fundamental to good corporate governance and being held accountable. However, one size does not fit all and there lies the reason why policy, framework and succession are so important for director tenure.

The Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) does not impose a limit on the tenure of a director. However, an organisation may impose its own tenure limits, for example, in its constitution, board charter or another policy. Further, regulators and good practice guidance recommend director tenure be considered when re-appointing directors.

For example, Box 1 shows the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority’s (APRA) requirement for a board renewal policy.

Box 1: APRA Prudential Standard CPS 510 Governance extract1

Similarly, Principle 3 of the Australian Institute of Company Directors’ (AICD) Not-for-Profit Governance Principles includes the tenure of directors in subprinciple 3.2 (see Box 2).

Box 2: AICD NFP Governance Principles extract2

Tenure limits

Many governance authorities recommend a limitation on the length of service of a director for two reasons:

- The concern that independent directors may lose the independence and the external viewpoint that they were intended to bring to the board if they remain on a board for an extended period. This can be as a result of becoming ‘too trusting’ of particular executives (or to a lesser extent by alignment to a faction of a board).

- Some commentators voice a concern that a long-serving director’s contribution and usefulness may wane (for example, as a result of running out of new ideas) or become less relevant to the organisation’s future.3

Term limits dictate that a director must retire after a set number of years, for example, 9 (i.e., 3 terms of 3 years) and 12 years for a chair. Beyond term limits, an important aspect of board composition is the tenure profile of the directors. A short average tenure might indicate instability and raise concerns around board dynamics, as well as the experience, skills and corporate ‘memory’. However, an unreasonably long average tenure might suggest a lack of independence and insufficient diversity of perspectives in board decision making.

Limits on tenure can be a great tool for organisations to appoint directors with fresh perspectives and from diverse backgrounds who bring a different approach. It can also be useful for removing those who no longer have relevant skills, are disruptive, or no longer contribute to board effectiveness.4

There are disadvantages associated with too much boardroom turnover because it may rob the board of valuable experience, skills, and organisational knowledge. However, this should not be used as an argument against board renewal through director term limits. Table 1 sets out a selection of the arguments often used against tenure limits and what the board can do to neutralise those arguments.

Table 1: Arguments against tenure limits and responses

Argument |

Response |

|

Loss of specific skills, knowledge and experience |

|

|

Loss of corporate memory |

|

|

Time taken for a new director to add value |

|

|

Board dynamics disrupted |

|

Is it a risk?

A 2019 US study6 analysed a sample of more than 3,000 companies over an 18-year period finding that board tenure is positively related to forward-looking measures of market value, but that positive relationship tended to reverse after about 9 years on average, when a director ‘might become stale and less relevant to the needs of the firm.’7 This is not a new finding, with earlier research showing that extended tenure is linked to a resistance to change and cognitive entrenchment,8 which describes what psychologists observe when people gain deeper expertise in an area but also become less flexible in their thinking.9

However, the balanced approach Elms and Pugliese take can be an appropriate one if in the best interest of the company:

… any blanket rule that limits the amount of time directors can remain on a board may have adverse effects to the corporation if a director is forced to retire while still in their prime. Rather than ‘dismissing’ long-tenured directors based on their tenure alone we suggest that directors’ capacities to contribute are best evaluated on a case-by-case basis.10

Directors should exercise due care and diligence when making any decision, including the board renewal process to ensure the board is made up of the right people with the right skills which may be both new and longer-term directors.

Boards typically avoid discussions about succession – chair, director, and CEO succession. This is a risk which should and can be avoided through fearless board discussion, board policy and clear board expectations.

Board renewal

A robust board renewal process built around the concept of performance management, including skills analysis and board evaluations will create a culture of accountability and improve board effectiveness.

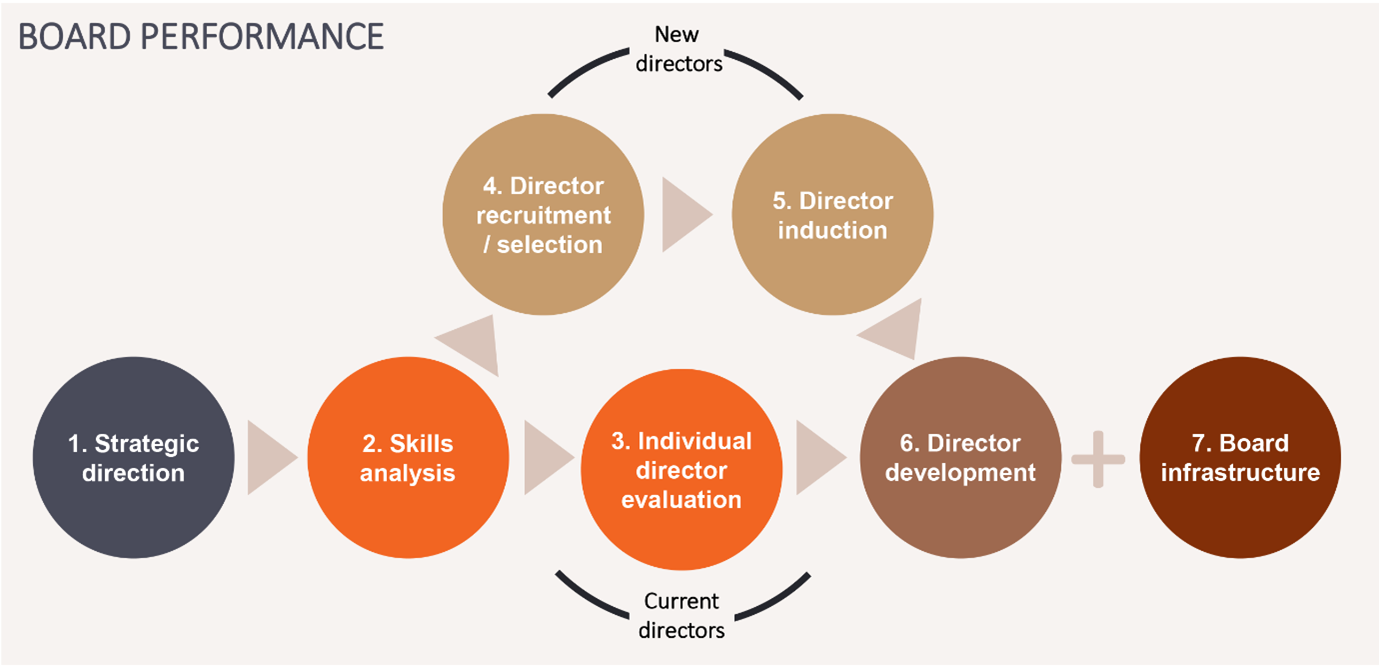

Figure 1 illustrates a board renewal process that includes:

- reviewing the strategy to determine the skills and competencies required on the board;

- individual self and peer evaluation for incumbent directors;11

- director recruitment and selection for new directors;

- director induction or orientation; and

- director development/education – includes coaching, mentoring, professional development programs.

Figure 1: Board renewal process

Studies show that each of these factors result in more competent directors and as a result a more effective board. These activities must be supported by a solid board infrastructure, which includes meeting processes and governance policies and procedures.

Conclusion

Embedding a risk culture into the organisation and the board includes ensuring the board has a robust board renewal framework and policy in place. So, what does an ideal director tenure look like? The answer is it depends – it depends on the individual director capability and capacity, the board expectations of its directors, the alignment of skills, competencies, background and experience with the organisation’s strategic direction, the demands of stakeholders and shareholders, the environment in which the organisation operates including size, complexity and maturity and importantly, directors acting in the best interest of the company and understanding where they owe a duty.

All boards will benefit long-term from a board composition policy that enables a healthy rotation of talented and engaged directors in the boardroom. Whatever the board decides, the key requirement is that continued service on a board must be adequately justified and explained. Careful assessments of the board’s skills and board and director effectiveness and behaviour are more likely to contribute to organisational performance than automatic term limits.

If you would like to discuss board renewal, director tenure or have any other questions, please contact our team for more information.

1. Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, 2022, Prudential Standard CPS 510 Governance, accessed 28 September 2023.

2. Australian Institute of Company Directors, 2019, Not-for-Profit Governance Principles, AICD, Sydney, accessed 28 September 2023.

3. Kiel, G., Nicholson, G., Tunny, J.A. & Beck, J., 2012, Directors at Work: A Practical Guide for Boards, Thomson Reuters, Sydney.

4. Boards should not ‘wait out’ a poor performer’s term and, instead, should be prepared to ask them to resign before their terms are finished. The outcomes of a self and peer evaluation can provide the chair with the evidence they need to recommend resignation to such a director.

5. A board that adopts a staggered board rotation will be re-electing or retiring one-third of the board each year. In some cases, a time-limited director to may be eligible to be re-elected to the board, but they should be assessed against the board skills matrix and undergo a self and peer director evaluation.

6. Livnat, J., Smith, G., Suslava, K. & Tarlie, M., 2019, ‘Do directors have a use-by date? Examining the impact of board tenure on firm performance’, American Journal of Management, vol. 19, no. 2, pp. 97‒125.

7. Ibid., p. 98.

8. See, for example, Golden, B.R. & Zajac, E.J., 2001, ‘When will boards influence strategy? inclination × power = strategic change’, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 22, no. 12, pp. 1087‒1111; Brown, J.A., Anderson, A., Salas, J.M. & Ward, A.J., 2017, ‘Do investors care about director tenure? Insights from executive cognition and social capital theories’, Organization Science, vol. 28, no. 3, pp. 471-94.

9. Dane, E., 2010, ‘Reconsidering the trade-off between expertise and flexibility: A cognitive entrenchment perspective’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 579‒603.

10. Elms, N. & Pugliese, A., 2023, ‘Director tenure and contribution to board task performance: A time and contingency perspective’, Long Range Planning, vol. 56, no. 1, p. 1‒17 at p. 14.

11. On the benefits of individual director evaluation, see Kiel, G., Nicholson, G., Tunny, J. & Beck, J., 2018, Reviewing Your Board: A Guide to Board and Director Evaluation, Australian Institute of Company Directors, Sydney, pp. 58‒60.