A common refrain I hear from CEOs and senior managers when discussing their boards is that they micromanage, i.e. the directors delve too deeply into operational matters. This is not only frustrating to management, but wastes the board members’ often limited time to do their actual job – directing, NOT managing the organisation. Worse still, this type of behaviour raises the perception that the board lacks trust in the management, which can have serious consequences including management deliberately holding back information, the loss of morale and the loss of key managers. Further, by not concentrating on governance and strategic matters, a board that micromanages can undermine organisational performance. For example, this can be through delayed decision making and missed opportunities as directors pore over the minutiae of management proposals and seek even more detailed information.

Micromanagement occurs where directors fail to recognise the difference between ‘governing’ and ‘managing’ the organisation (see table 1). This can be for a number of reasons. While the legal framework for corporate governance means that directors must be informed about the operational aspects of the organisation and engaged in the strategy process, they delegate responsibility for the day-to-day running of the organisation to management. Without clear role descriptions for both the board and individual members, directors will often carry over their day jobs as managers into the boardroom, i.e. they are more accustomed to ‘doing’ than ‘delegating’ or ‘leading’. This can be overcome by reviewing the board charter to ensure the board’s responsibilities and those of directors are clearly spelled out. If the board does not currently have a charter, the development process would be a good opportunity to highlight the role of the board as opposed to that of management.

A sound induction process is ideally where new directors are given a proper understanding of the delineation between the role of management and the role of the board, however, this is an area where many boards fail. Properly inducting new directors enables them to exercise their duty of care and participate fully in board activities from their first board meeting, so a review of the process may be warranted if it is not achieving its purpose.

The CEO can sometimes facilitate a board’s propensity for micromanagement by presenting the board with reports designed for managers rather than directors, although the board too is culpable here, because the directors should be telling management what they expect in terms of board papers. See our board paper template for how to streamline the board papers. On the one hand, poorly presented board papers are frustrating for directors who may believe the management team is trying to cover something up if they are deluged with too much information, but on the other hand, a plethora of data can focus the board too heavily on operational matters.

Having the board set a series of KPIs – both financial and non-financial – which can be presented in a dashboard format will allow the board to monitor the organisation’s health and progress in achieving it strategic objectives is another way to get away from an overly operational board.

Table 1: Governance vs. management roles

| Governance roles | Management role |

Directors direct |

Managers manage |

While board committees are expected to deal with matters in more detail than the board as a whole such as the audit committee, they can also invite micromanagement when their terms of reference from the board are too broad. This is especially the case where the committee deals with an administrative or operational function such as product or program development. Regularly reviewing committee terms of reference will ensure the committee’s scope of work and the product the committee will generate (e.g. advice, written recommendations/decisions) are clear.

The chair is in the best position to change the board’s focus from operational to governance matters. For example, the introduction of a strategic agenda rather than a traditional agenda will ensure the type of items that are placed on the agenda are not those that invite micromanagement and that the agenda contains strategic or ‘big picture’ items.

Governance arrangements for most organisations will emphasise the role of the board in developing, monitoring and reviewing policies. The board is only meant to do this at the governance level, since involvement in the entire policy framework of the organisation could become a burden for the board as well as leaving the board open to criticisms of micromanagement. Therefore, the board needs to distinguish between governance and operational policies. Governance policies predominantly focus on furthering the organisation’s strategic direction, ensuring compliance, reducing risk to the organisation and the community, and on the operations of the board such as through the development of the board’s charter. While the board has to make sure the organisation has appropriate operational policies in place, it does not need to develop or even review all those policies. Policies and procedures dealing with operational matters are generally delegated to the CEO.

Delegation of authority – a subset of the policy framework – is another area where the board can go astray. While the board should assess the risk to the organisation of each delegation, delegations cannot be so low as to require board approval for expenses such as the electricity or rent. However, the limit should not be so high that the capacity of the organisation to operate within its budget is compromised. Therefore, it is essential to have regular monitoring and reporting processes, including reviews and risk management assessments of board delegations.

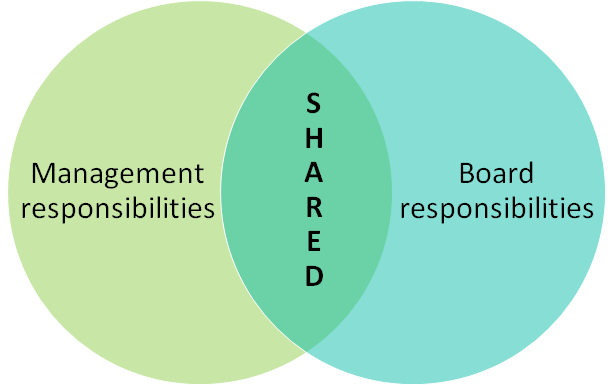

However, it should be noted that in some circumstances the board will be required to delve into the operational side of the organisation. As shown in figure 1, this is especially the case in smaller organisations. Indeed, in very small organisations such as not-for-profits with few staff members, it will likely be expected that the board will take a more managerial role. The other situation is during a crisis when the board, and especially the chair and directors with specific skills, can be called upon to take a more hands-on role. For example, a scandal involving members of the senior executive team such as bribery or fraud may necessitate the chair stepping into the CEO’s position.

Figure 1: Governance vs. management roles

Smaller organisations

Larger organisations

Adapted from Falls, N., 2015, Corporate Concinnity in the Boardroom: 10 Imperatives to Drive High Performing Companies, Austin, TX: Greenleaf Book Group Press, p. 28.

An understanding of the difference between governance and management is key to overcoming a board that micromanages. If you see this happening on your board, I would advise that you give feedback to chair if you are a director, the CEO or company secretary, and to the board as whole if you are the chair. Micromanagement helps no one and, as noted above, can be harmful to the organisation as a whole.